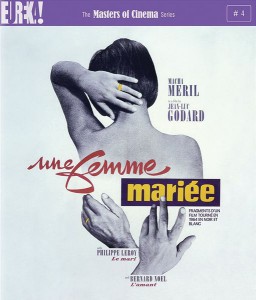

Charlotte is young and modern, not a hair out of place, superficial, cool; she reads fashion magazines – does she have the perfect bust? She lives in a Paris suburb with her son and her …

Director: Jean-Luc Godard

Writer: Jean-Luc Godard

Actors: Bernard Noël, Macha Méril, Philippe Leroy, Christophe Bourseiller

With A Married Woman, Jean-Luc Godard leeches a story of a bored, attractive, unfaithful housewife of much of its escapist luridness, favoring ennui over sex, symbols and signifiers over narrative. The film is remarkably chilly and precise even for the legendary director, providing a peek at where his career would head after his run of comparatively quasi-populist 1960s-era hallmarks. A Married Woman is exhilarating in its masterful suggestion of how fictional films could formally evolve, utilizing documentary and image and narrative fragmentation in fashions that have proven to be greatly influential.

The film’s first image is a resonant shot of a male arm grasping a female wrist. The intersection of the arms forms a right angle, suggesting the hammer and sickle associated with communist societies. Charlotte (Macha Méril) is introduced one body part at a time. After her arm, we see her stomach, her shapely legs, and eventually her face. Godard literally objectifies Charlotte, then, reducing her to detached portions. Charlotte is intensely tactile to us as a series of fleshy still lifes, as we can see her right down to her pores and feel the pleasure the male arm and hand take in touching and squeezing her.

Godard gradually grants Charlotte agency of being, though the same can’t be said of her lover, Robert (Bernard Noël), who’s faceless for most of the opening before existing, like her husband, Pierre (Philippe Leroy), as a foil for the remainder of the running time. The implication of this schematic, virtuosic framing is pointed: Godard parodies our sexual obsession with a certain kind of bored bourgeoisie woman, deliberately fashioning poses that resemble advertisements that pray on our fantasies, though enjoying her nevertheless, while suggesting that Robert could be any man. Godard might also be parodying his own aesthetic, self-digesting it, riffing on his searing, ticklish artiness, and perhaps on the fact that we’ve already been to this territory many times before with him.

There are few things that Godard likes to do more, in his 1960s-era cinema, than cordon two privileged, good-looking lovers off in a stylish room together and have them pontificate on high- and low-brow culture in a postmodern manner that suggests the detonation of culture. Interspersed with these digressions are thoughts on love that are so banal they’re either meant to be ironic, to be taken with a straight face, or, most interestingly, both.

A Married Woman finds Godard at a fascinating crossroads. He seems to distrust the intoxication of his earlier films at this juncture, the way they pointed toward an intellectualized pop culture that served to ultimately enhance the pleasures of pop for self-conscious eggheads who took the director to be to cinema what Bob Dylan was for music near the same time in history: a paradoxically populist rebel. The purplish lushness of Contempt is nowhere to be found in A Married Woman, which is shot in a gritty black and white and composed of hard angular imagery. Godard’s Marxist leanings are more explicit in this film than at any point before, as that angularity is intended as an alienating effect meant to explicate the film’s messages. Yet the filmmaker still gets off on pop culture, affluence, beautiful women, and a certain je nais se quoi of the wandering French male who indulges all those things.

This unresolved element of his sensibility is most evident in one of the film’s best scenes. Charlotte looks at a fashion magazine while Sylvie Vartan’s “Quand le Film Est Trist” plays on the soundtrack, the filmmaker turning a potentially simple placeholder between bigger moments into a major sequence onto itself. Charlotte gazes at pictures of lingerie, as the song gives the extended sequence a cheeky bounce. Godard resents the way society tells women to contort themselves for a man’s pleasure, as this sequence connects to the bald objectification of the opening scene, and to a male character’s observation that women spend more time considering how to please men than themselves. Yet the lingerie scene is also sexy, reveling in an attractive woman’s casual time-killing as an act of voyeurism, turning a taken-for-granted action (flipping through a catalogue) into a revealing glimpse into how we’re encouraged to spy on one another for the sake of envy and titillation, fueling commercialism, which extends to the titillation of A Married Woman.

Godard’s didacticism threatens to get the better of him. (As is usually the case in his work, the filmmaker’s ideological messages are nowhere near as revelatory as his dense, discordant, found-object-laden aesthetic.) A moment in which Charlotte is revealed to barely understand the significance of Auschwitz is obvious and cruel as staged, scoring points on the ignorance of the masses (especially women) to historic atrocity. A long, potentially ironic sermon on the strength of intellectualism is powerful on its own oratorical terms, but cumulatively threatens to beat a dead thematic horse.

A Married Woman is haunting less for its social critiques than for the way Godard puts us in Charlotte’s head space. He offers few expository details about her, yet we suspect by the end of the film that we know Charlotte, as she’s vividly defined by her reactions to objects like the lingerie magazine, or to the way men touch her. Even when Charlotte’s face is so separated from other elements within a scene as to purposefully evoke the Kuleshov effect, we feel her. Godard captures the tragedy of the suggestion that we’re nothing more or less than the sum of our consumptions, which collectively establish our personality, or, to use a postmodern term, our “brand.”

BRRip | MKV | 768 x 576 | AVC @ 2542 Kbps | 95 min | 1.83 Gb

Audio: French AC3 1.0 @ 192 Kbps | Subs: English (embedded)

Genre: Drama | France